At the Intersection of Technology, AI, and Investigative Journalism: Lessons from GIJC 2025

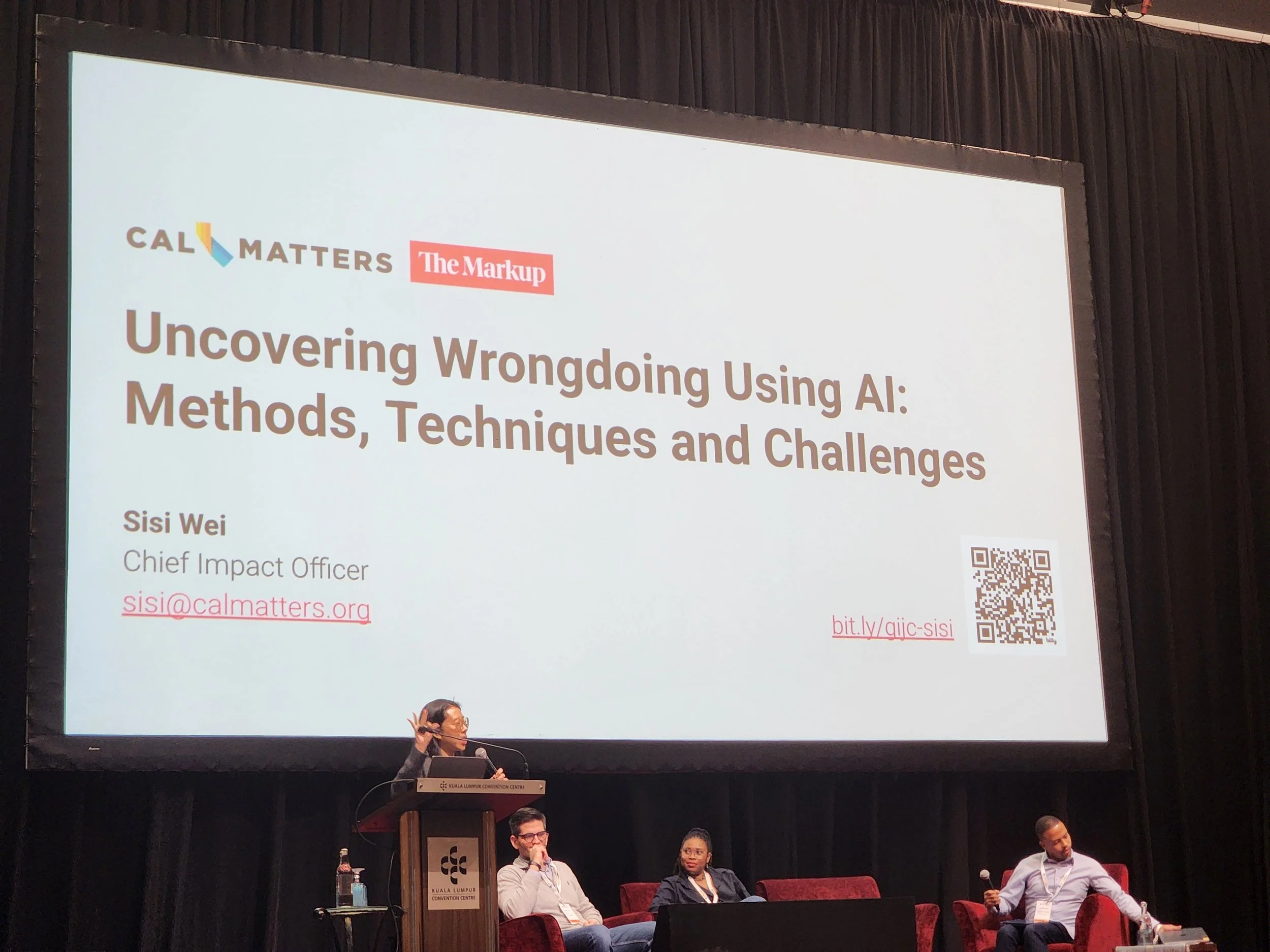

From the Panel “Uncovering Wrongdoing Using AI: Methods, Techniques and Challenges” at GIJC25

In 2025, I attended the Global Investigative Journalism Conference (GIJC) in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, as a Technology and AI Fellow with the Global Investigative Journalism Network and Malaysiakini. The fellowship came at a pivotal moment in my journey: less than a month earlier, I had founded Anmat, a project focused on using machine learning algorithms to detect, analyze, and quantify bias in media and textual narratives.

What stayed with me most after the conference was not only how fast technological tools are evolving in investigative reporting, but also how many journalists from different backgrounds, ethnicities, and regions are already working at the center of this transformation. Their work made one thing very clear: technology and AI are no longer optional skills at the edges of journalism. They are increasingly shaping how investigations begin, develop, and reach audiences.

Throughout the week, I encountered projects that stretched my understanding of what investigative journalism can look like today. Some focused on uncovering algorithmic bias itself. Others used computational methods to prove illegal mining activities. One investigation analyzed how urban populations’ access to sunlight is shaped by planning decisions. These stories, coming from both the Global North and the Global South, pushed me to think more concretely about where Anmat can go next.

Below are the lessons that stayed with me most, and that I believe are worth sharing with the journalism community.

Technology Does Not Remove Inequality, But It Can Narrow It

One of the realities repeatedly acknowledged during the conference is that technology does not automatically level the playing field. The cost of innovation, access to structured data, and infrastructure gaps still give many Global North newsrooms a significant head start in developing new investigative methods.

These divisions even exist within the same countries, separating local newsrooms from national and international ones.

Yet what I witnessed at GIJC25 showed that responsible and creative uses of AI can begin to close parts of this gap. In panels such as “Uncovering Wrongdoing Using AI: Methods, Techniques and Challenges,” speakers demonstrated how technology can support accountability journalism in practical ways.

CalMatters showed how AI tools strengthened investigations aimed at holding local representatives in California, US accountable and empowered local journalists to produce quality stories, while also helping citizens understand how their elected officials perform during public hearings, addressing resource gaps that often limit local newsrooms.

In another example, Nelly Kalu from the Center for Collaborative Investigative Journalism (CCIJ) presented how AI was used to counter misinformation during elections in Nigeria. The project transforms investigative stories into interactive virtual exhibitions inside the Voxels metaverse, allowing audiences to explore data, visuals, and narratives within a three dimensional environment. It is part of a broader initiative to use virtual and augmented reality technologies to create new ways for the public to engage with data driven investigations and understand complex reporting.

Seeing such different contexts side by side made one idea stand out: technology becomes empowering only when it is directed toward clear public interest purposes.

In Tech Driven Journalism, Openness Is Not Optional

A recurring theme throughout the AI focused discussions was transparency, not just as a value, but as a working method.

Panelists like Sisi Wei from CalMatters and Fabrizio Palumbo from the AI Journalism Resource Center spoke about sharing the code behind their work. What struck me was that this practice was not framed only as an ethical gesture. It was described as a necessity for reproducibility, allowing journalists elsewhere to verify, adapt, and build upon investigative methodologies.

Having spent more than a year studying data science virtually among engineers, this felt familiar. Technical communities thrive on collaboration and the ability to reproduce each other’s work, not to copy, but to test, improve, and extend it. As journalism increasingly intersects with technology, these same principles are becoming essential for maintaining credibility and collective progress.

Collaboration Across Borders Is Becoming a Survival Strategy

Another lesson that stayed with me is how deeply investigative journalism now depends on collaboration beyond national boundaries.

Independent newsrooms are facing increasing financial uncertainty, including disruptions linked to shifts in international funding. During the conference, many founders and editors spoke openly about how they are navigating these challenges. One of the most consistent strategies shared was collaboration, not as an ideal, but as a practical survival mechanism.

Many of the most ambitious projects presented at GIJC25 were born from partnerships that crossed regions, languages, and institutions. These collaborations allow journalists to access tools they may not have locally, expand investigations across borders, and build support networks around difficult stories. This can be seen in the collaborations behind Agência Pública’s AI related work, as well as partnerships developed by the AI Journalism Resource Center with Norwegian newsrooms to support tech driven investigative reporting.

In many cases, collaboration is no longer simply beneficial. It is what makes certain investigations possible at all. This lesson also reinforced confidence in what we are doing at Anmat, where we collaborate with several newsrooms to help them analyze textual data across the NENA region and beyond. These collaborations, which we began pursuing during and after GIJC25, build directly on this insight. It is a risk given our limited resources as a small initiative, but the impact I have witnessed makes it a worthwhile one.

AI Tools Reflect the Worlds They Are Trained On

From Hasina Gori’s Presentation

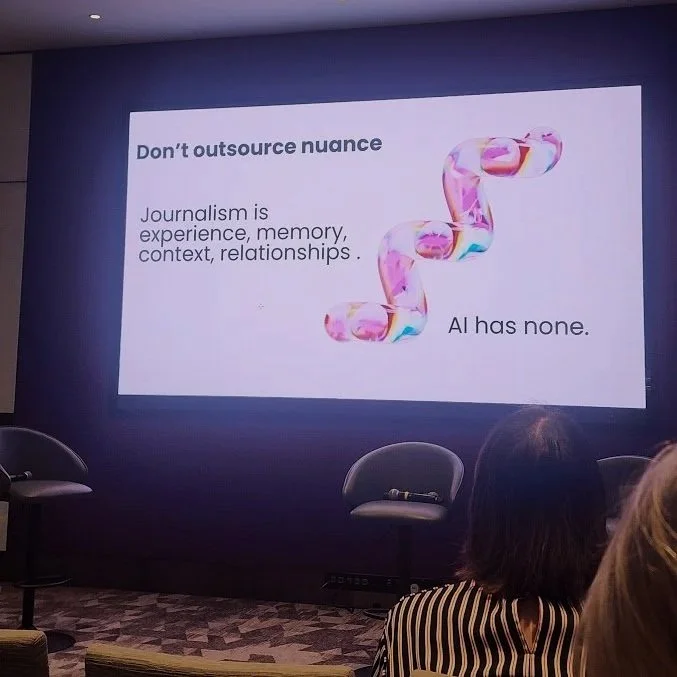

One of the lessons that resonated with me most came from discussions about generative AI and its limitations. Research presented by Hasina Gori highlighted how many widely used AI models still struggle to represent Global South languages, cultures, and social contexts, in short, our world.

Her work emphasized practical ways to navigate these gaps: treating AI as a tool rather than an authority, verifying every output, questioning training data sources, and recognizing that AI cannot replace lived experience or contextual knowledge.

For journalists working in environments like mine, these challenges are especially visible. Data may be incomplete or inaccessible, and AI systems often misinterpret local languages or realities. This creates a constant tension between technological promise and everyday usability.

At Anmat, we are not heavily reliant on generative AI, but we inevitably encounter it in our work. Supporting journalists and researchers who use our datasets requires guiding them on how to ensure AI tools complement their analysis rather than distort it.

What This Means for Anmat and Our Work Going Forward

The experience at GIJC25 did not simply introduce new tools or techniques. It shaped how I think about the role of projects like Anmat within the larger investigative ecosystem.

Within the project, we have long debated how to expand its impact beyond conflict reporting and initiatives such as “Framing Gaza.” The conversations and examples I encountered during the conference opened new ways of thinking about how our work could support a broader community of journalists and researchers, something we are already seeing through workshops and ongoing collaborations around stories built using our data, and we hope to build further on it through partnerships we have activated with organizations such as InfoTimes and the Arabi Fact-hub, among others. Through these partnerships, we aim to extend the knowledge we have developed to reach larger numbers of journalists and researchers.

It also helped answer a recurring question we ask ourselves: what is our added value to the investigative community? The answer lies in our unique position at the intersection of journalism and technology. As an investigative journalist, I understand newsroom needs; as someone working with data and machine learning, I can help translate technological possibilities into practical investigative tools and accessible datasets.

Months after returning from Kuala Lumpur to Cairo, I am still processing the lessons from that week. What remains most clear is that meaningful innovation in journalism is not driven by technology alone. It depends on persistence, collaboration, and the willingness to adapt tools to local realities rather than forcing local realities into tools built elsewhere.

With the right intentions, shared knowledge, and strong networks, technology can help investigative journalism become more accessible, not less, across borders, languages, and resource constraints.